Recalling a Day with the Pike

Recalling a Day with the Pike on the Roaring Mantiowish Years Ago

Omaha World Herald (Omaha, Nebraska, August 5, 1917)

Welcome to Discovering the Northwoods from the Manitowish Waters Historical Society. We will take you on a journey through our local history with the help of primary source documentation. To learn more about this rich history or about the historical society – check out our website at mwhistory.org. There you will find blog posts, show notes, our YouTube Channel, and a full transcription of this episode including maps and photographs.

As with many historical works from this era, there are phrases, terms, and descriptions that are inappropriate to our modern sensibilities. The Manitowish Waters Historical Society in no way condones these offensive remarks or passages. For this episode, we altered some of the offensive and derogatory phrases. The original document is attached in the show notes if you’d like to read this publication in its entirety for educational purposes and accurate historical context.

In this episode, we turn the clock back to August 1917, when a writer for the Omaha World Herald, Sammy Griswold, captured the memory of a single, unforgettable day deep in the wilds of Wisconsin. His destination? The roaring Manitowish Falls — a place where thundering waters met quiet solitude, where towering hemlocks cast shadows over the trail, and where a single cast could land you a prize from the swirling depths below.

This isn’t just a tale of fish and falls — it’s a story of the kind of day that etches itself into the memory forever, where time seems to pause in the hush of the forest and the roar of the river. From the wonderful narration of Sarah Krembs, we will dive into this historical account and explore what these experiences can teach us about the past.

Transcript

I can at least tell you of my experience with the pike, at the Manitowish Falls in Wisconsin, way back ten or more years ago, when I was up there as the guest of the late lamented– grand and glorious fellow that he was– Fred Nash. One evening, Mork, a guide of ours, and I, set out from our shack on the Boulder, for the falls where the man confided to me that I’d have the time of my life. And he was right. I did. He could only go far enough across the woods, to show me the way, so I wouldn’t get lost, as he had to be back to take care of others in the party, on the muskellunge trail the next morning.

We had been resting on the shores of a little blinkin’ lake, long as the sun was dropping low, and as we arose, and my guide said;

“Way off thereaways,” and he pointed off to the southeast with his rifle, “is Manitowish Falls, and when you get to the top of the next hill, a mile on, you’ll hear the roar. In the early spring, when there’s considerable high waters, the falls drum up quite a little thunder. The foam splashes over in big clouds. I’ve seen some mighty big trees dashin’ an’ quirlin’ and crashin’ over the rocks as if the lightnin’ had sent them; and once I saw a deer apirchin’ an a-strugling’ down the rapids, just like a loon’s feather pitchin’ in the riffles. He was dead enough, you can suspect when he hit the bottom. Well, off there’s the falls, as I was saying, but the dam’s way this side–you just keep this trail–don’t go to traveling off either to the right or left–and when you get to the top of the next big hill you’re as good as there. So long.”

And handing me the Winchester and my rod Mork turned on his heel and shot away down the long, sandy incline like a deer before the hounds. In such an evident hurry was he that he even failed to mention the little flask inside the minnow bucket.

I was soon on the road. Large masses of light and shade, cast by the wall of grim old hemlocks and Norway along the southern borders of the infrequently used trail, lay over my pathway. Beautiful little sunrise pictures gleamed out as I jogged along, a big messy rock; a tiny dingle, where the hen partridge clucked her babies in sweet content; a rapid rivulet, pouring toward the Manitowish; a colonnade of riven and blasted trees; an arbor of linked branches, a distant gleam of the flashing river, or a bit of boggy lowland where the tiger lilies curled among the spears of the rushes.

Postcard of Papoose Lodge from the Frank Koller Memorial Library. 2018.5.27.

A half hour’s diligent trudging and I climbed the long ascent to which the guide had referred, and with a suddenness that was at least a trifle startling, the voice of the falls burst upon my hearing. In my loneliness, I stood still for many movements, listening. The dull roar, however, was not long in adding a charm to the situation, and again picking up my bucket and shouldering rod and rifle, I eagerly resumed my tramp. A moment later, in rounding a long curve in the pine-lined trail, I abruptly came face to face with two deer, a big, thin, star-eyed doe and her hardly half-grown fawn. They had been following the road up the hill coming toward me, and so noiselessly had been my own advance downward, that they were unsuspecting of the proximity of anything so deadly as a man, until they were fairly and squarely face to face with me, hardly two dozen yards separating us.

There was an instantaneous halt on the part of both the deer and myself, but before I had time to stamp upon my memory this enchanting situation, a quick, sharp bleat struck my ears, and like a flash of reddish gray, both mother and fawn had vanished into the wall of green along the pathway. But I had gotten a good, full look at the pair, the doe as she became transfixed with fright, her great luminous eyes dilated wildly and her long ears cocked straight up ahead, and the little youngsters, with his selder white nozzle pushed under his dam’s belly, as if no threatened peril could reach it there, and then that sharp alarum, a whirls of gray and brown the closing gap of green, a flash or two of white in the deeper growth, and then naught but the golden sinuosities of the lonely trail, the blue above, and the universal walls of green all about me.

Another quarter of an hour gone and I was at last down in the deeper valley of the Manitowish, below the rapids of the dam, and at the edge of an old deserted loggers’ camp, which has stood there for years and years, in fact was built before a dam at this point was thought of.

I beat my way cautiously down the wild shore over a bed of gray boulders, where a natural cascade dashing and twisting in several channels between log, thicket and rock rushed roaring in a broader mass of foam down a sloping ledge, into the river itself, pushing its dancing bubbles of silver swiftly along the rolling surface till the jutting woods spoiled the view. Again I emerged into the trail and climbing another graceful acclivity, I arrived at a considerable clearing with the long, low tumble down long shanties of the old-time wood choppers fronting the noisy vortex of waters bursting from the open gate of the dam, which made the roar from the distant falls blend into a dull murmur. Below the main camp, a few feet above the river’s edge, was a spring about four feet around, boiling clear as dew and cold as ice, from a deep bed of slaty rock and sand.

Overshadowing all other interests of my lonely summer day jaunt through the big woods on my way to the Manitowish Falls was my anxiety over what my experience would be when I reached my destination, so after the guide’s leaving me I hurried on and early in the evening found myself there. I was a bit travel-worn, but after a brief blowing spell, I knelt down and took a long, refreshing draught from the spring at my feet, then gathered up my traps proceeded along a well-beaten path from the shanties up over the log lock of the dam and out upon a great pile of the same to a point overlooking the boiling maelstrom from the big gates. After feasting my eye upon the wild and novel scene, I got ready and tried to do a little casting, more as a pastime than with any hope of accomplishing anything. I had never fished in such a place before and knew absolutely nothing about how to go at it. But I remembered that Henri had said that the pike were in the boiling avalanche, and I intended to investigate for myself.

Hanging the minnow bucket on a convenient cedar snag, and laying the landing net on the logs beside me, I hooked a minnow upon the tripod of hooks and sent the silver-backed, scarlet-bedded spoon whirling out over the sudsy waters, plump into the thick of the torrent. Before I could hardly realize it the force of that tremendous current had taken almost all of my whizzing reel and brought up with a sudden jerk in the slower swirling waters below, where the plunging of the whirlpool had spent its force.

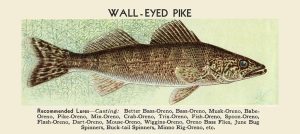

I began to slowly windlass in my line, thinking, of course, as I dragged it through the comparatively quiet shallows along the shore, that I had some fragment of a branch or bunch of weeds for my pains until within about twenty yards of my perch, and just where the waters from the dam began to viciously boil again, a splendid black, mottled fish – I couldn’t determine what kind–broke the water several times, glinting in the sunshine like a curve of gold, and I discovered that he was fastened to my hook. I was a quiver with the most pleasurable excitement in an instant, and at once bent all my energies to landing him. This while the fish struggled gamely, was not so difficult as I imagined it would be, and in the course of a very brief space of time I had him cavorting in the clear, amber waters close to the logs at my feet. One or two ineffectual attempts, and then I succeeded in slipping it into the landing net, and lifted out upon the dead cedars a magnificent four-pound walleyed pike. It was a grand fish in its armor of black, gold-dotted scales, and so elated was I that before disgorging the hook I lifted him up and ran out along the logs to the grassy shore, stringing the line out recklessly behind me.

I had him off the hook and on a stringer in a jiffy, and then after examining it closely I wound the stringer around a depending branch of an overhanging bush, and leaving it dangling in its native element back, wound up on my line, impaled a minnow on the hook and once more proceeded like a native-born about my business.

Let me observe here, by the way of parentheses, that my catch was a veritable walleyed pike, differing only from the same fish caught in the waters of the open lake by its coloration, general black, with topaz dots on the back and side scales, a result of the cedar and hemlock stained waters of the dam.

But it would become a wearisome story, I wrote to recount in detail the thrilling battles– each one a repetition of the other, with inconsequential variations–I had with each succeeding fish. With the statement that in the two hours, I sat and crouched there, industriously casting all the while, that I logged thirty-one beautiful pike, several of them running up to six pounds and over, and seldom one less than three. I’ll leave the scene to the imagination of the reader. I will add, however, that I made but few casts without getting a strike, and while an occasional especially plucky fellow got away from me, I landed a big majority of them. It was the hardest kind of work, but thrilling at the same time to the marrow, and I must say was a fishing experience that will linger in memory as long as memory lasts. In open water, and from a boat, I could have landed 100 fish of the same kind, in the same time, had they bitten like these did, but on a precarious perch on a pile of logs such as I occupied, I was sorely hampered, and it required three times the time to land a fish it would under ordinary circumstances. Holding a fighting pike taut on a short line in a pool of swirling water, with one hand, and manipulating the landing net with the other, was no child’s play.

Wall-eyed Pike Illustration from Interior Element, Eagle, WI.

Finally, I grew surfeited with the nerve-tingling exercise and crawled upon the needly shore and lay down to rest, and now I wish for one or two or three of my old hunting pals at the shack. I felt it was something they had never enjoyed, not even in their long and varied careers, and I knew with what robust zeal and bounding spirits they would have entered into it. But they were miles and miles away trolling on the glassy lake for that phantom of the watery wilds, the muskellunge, and I dismissed them from my thoughts and lay and gazed and dreamed away those lonely, but happy summer hours, all alone.

Beautiful and bright came the fullness of the day, suffusing the torrent, the rushful river, the lumberman’s camp and the forest with a cheery beauty seen nowhere far from nature’s thoracic region.

The morning’s sunlight in the north woods has a profound splendor, I always thought not shared by that of the sunset though lovely as that always is, the former, fresh from heaven, seems gladdened in obeying the behest of the creator, while a sadness that would darken all its radiance, were it not for the joy of its hidden ministry for the time was ended, and it was leaving, if but for a few brief hours, a world it had illumined only to behold its follies, foibles, and crimes.

A little after noon, I emptied the few minnows I had left into the torrent knowing that I could shoot a blackbird for bait, if I needed more, or catch all the fish a man ought to with the naked spoon, and rinsing the bucket, went back over the lock, down to spring and filling the same with icy water, climbed back up the hill to the camp, and in the shade of one of the shanties, ate my lunch. And it was a lunch, too, to make the mouth of even the pampered gastronome water with delight.

In a short space of time I had a fire startled, over which one of those pike I had taken from the dam was soon hissing, impaled on a forked stick. To the wild clatter and hissing of the dam and the dull roar of the falls, I devoured my meal.

The eastern sky, notwithstanding the rainy nature of the morning, was now overcast with a thin gauze, that suggested rain. Against this lowering background, here and there, a tall withered pine above the general foliage thrust itself skyward and in one of which I discovered another hawk’s nest, like a Doric column with its capital. Stretching away from my feet way down the wild Manitowish the whole dark valley was etherealized in the dreamy haze of noontide.

Worn out with my long morning tramp, and the ardor of my casting from that loggy pyramid, and with my general lassitude enhanced by my lonely but sumptuous repast. I finally fell back upon the soft sward and began to muse over the many phases of a one’s life. And as I lay there in that wild solitude, I could not help but think of the one above us all. How near he appeared and how distant man!

The north woods is one great tongue, speaking constantly to our hearts, inciting knowledge of ourselves and to love of the father. Not in the burning waste of the desert, nor on the mighty billows of the deep, do we more profoundly realize the one presence that pervades the loneliest recesses of the world. Here with the black woods for our worshiping temple, our hearts expanding, our thoughts rising unfettered, we behold him face to face.

Surrendering myself to such thoughts and to the hour and scene, lulled by the turmoil of angry waters, I fell asleep.